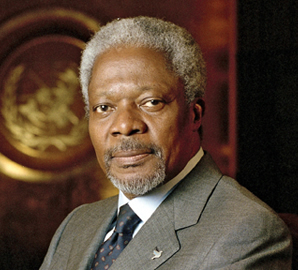

Kofi Annan, the seventh Secretary-General of the United Nations, spoke at a Jackson Institute Town Hall meeting held in the Yale Law School on February 7. In his signature calm and deliberate manner, Annan recounted personal stories during his time in the U.N., and addressed issues from Security Council reform to the civil war in Syria and the development of Africa.

“I had a teacher in boarding school who took out a one-meter-by-one-meter sheet of paper and drew a black dot on it, and asked what we all saw,” Annan said, describing one of his most formative experiences as a child. “All the students in the room shouted out, ‘the black dot.’ The teacher stopped and said, ‘Everyone saw the black dot, but no one saw the big white sheet of paper. Don’t go through life focusing on the negatives.’”

Annan also identified his upbringing in Ghana during a period of turmoil as a major influence on his life, as it made him believe that change was possible. He also mentioned his move from Ghana to the United States in order to attend Macalester College. “I hated earmuffs, because I thought there were very inelegant,” Annan said, talking about the cold Minnesota winter to much laughter. “One day, I went out to eat and nearly lost both of my ears. The next day I went and bought the biggest earmuffs possible.”

What he learned from that experience, he said, was that “you don’t just walk into an environment and think you know better than the natives. You must listen to them.”

The Town Hall meeting, which was moderated by John Negroponte, the Brady-Johnson Distinguished Practitioner in Grand Strategy at Yale, senior fellow at the Jackson Institute at Yale and former United States Deputy Secretary of State, was in commemoration of the publication of a 5-volume set of Annan’s documents and memos from his time at the U.N. Jean Krasno, a Distinguished Fellow for International Security Studies at Yale, spearheaded the project to declassify and publish these documents.

The talk was largely focused on U.N. reform, especially concerning peacekeeping and humanitarian interventions.

“The approach during my time was to focus much more on the individual,” Annan said. “Most people saw the U.N. as an organization of sovereign member states, but if you really look at the structure at the time it was set up, the entire idea was to protect individuals.” Even on issues of borders, the role of the U.N. was to protect the livelihoods of citizens, not of the states, he said.

He went on to defend the U.N. against attacks on its inefficiency and slow decision-making processes, especially in the Security Council.

When things go wrong, he says, people blame the U.N. as if it were a separate entity. But the U.N. is “ultimately as good as its member states.” He added that when people put blame on the U.N. itself, it deflects responsibility away from the governments that are stalling the process.

He also explained that the influence of the U.N. was far more than issues of conflict. “If it weren’t for international agreements that standardize communications, or rules about intellectual property, or maritime conduct, our lives would be impossible,” he said.

During the rest of the Town Hall, Annan addressed climate change, Africa’s rapid development, his failure to achieve peace in Syria as an envoy, and U.N. reform—on which he told a story about a meeting he had with the members of the Security Council when he failed to get reform passed in his self-imposed six-week time period.

“I got up and apologized for not getting U.N. reform passed,” Annan said. “And then Sergey Lavrov from Russia stood up and said, ‘God took a shorter time than you to create the entire world.’”

“I replied, ‘But God had the opportunity to work alone,’” Annan recounted, to laughter in the audience.

For all the humor behind this story, there lies a kernel of truth about the difficulty of reforming the U.N. “I have learned in my life that there are two things that people don’t like to give up: subsidies and privileges,” Annan explained. “The privileged few in the U.N. must come together to see how much power they are willing to give up in order to achieve real cooperation—real cooperation instead of destructive competition.”