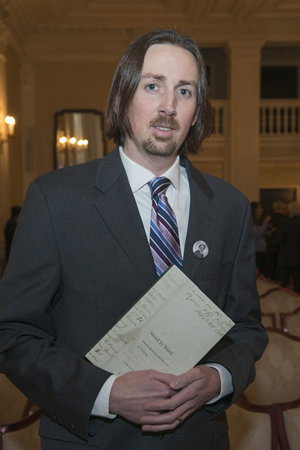

Christopher Hager worked on Word By Word: Emancipation and the Act of Writing (Harvard University Press, 2013) for about six years. On January 29, 2015, at the Yale Club of New York City, his book won the Sixteenth Annual Frederick Douglass Book Prize for the most outstanding nonfiction book in English on the subject of slavery and/or abolition and antislavery movements. The $25,000 Douglass Prize, created jointly by Yale University’s Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition and the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, was established in 1999 to stimulate scholarship in the field of slavery and abolition by honoring outstanding books on the subject.

More than 150 people attended the award ceremony and reception at the Yale Club. James Basker, President of the Gilder Lehrman Institute, welcomed the guests and introduced students from New York City high schools, who read passages written by Frederick Douglass. David Blight, GLC Director and Class of 1954 Professor of American History, then took the stage, honored the finalists and presented the Douglass Prize to Christopher Hager. Hager was “deeply honored” and delivered a remarkable speech about making the lives and legacies of slaves and former slaves legible.

In addition to Hager, the other finalists for the prize were Camillia Cowling for Conceiving Freedom: Women of Color, Gender, and the Abolition of Slavery in Havana and Rio de Janeiro (University of North Carolina Press, 2013), and Alan Taylor for The Internal Enemy: Slavery and War in Virginia, 1772–1832 (W. W. Norton, 2014).

A review committee of representatives from the Gilder Lehrman Center, the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, and Yale University met with the jury in October and chose the winner. “Christopher Hager’s Word By Word presents a profoundly original, illuminating approach to reading texts by and about enslaved African Americans,” commented the jury. It “shows how texts written—and, often, revealingly, rewritten—for particular purposes articulate their enslaved authors’ broader understandings of, and investments in, family, romantic love, selfhood, and politics. What emerge are the voices of highly individualized enslaved people as they negotiate intersecting networks of labor, power, and kinship.”