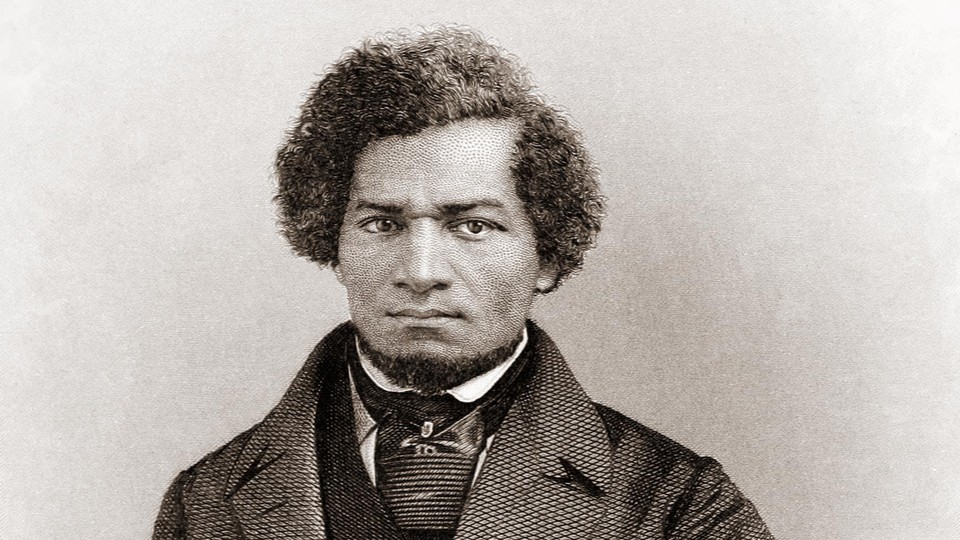

Frederick Douglass, Refugee

Throughout modern history, the millions forced to flee as refugees and beg for asylum have felt Douglass’s agony, and thought his thoughts.

Frederick Douglass, author, orator, editor, and most important African American leader of the 19th century, was a dangerous illegal immigrant. Well, in 1838 he escaped a thoroughly legal system of enslavement to the tenuous condition of fugitive resident of a northern state that had outlawed slavery, but could only protect his “freedom” outside of the law.

Douglass’s life and work serve as a striking symbol of one of the first major refugee crises in our history. From the 1830s through the 1850s, the many thousands of runaway slaves, like Douglass, who escaped into the North, into Canada, or Mexico put enormous pressure on those places’ political systems. The presence and contested status of fugitive slaves polarized voters in elections; they were the primary subject of major legislation such as the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 as well as Supreme Court decisions such as Dred Scott v. Sanford in 1857. They were at the heart of a politics of fear in the 1850s that led to disunion. Among the many legacies of Douglass’s life and writings alive today, one of the most potent is his role as an illegal migrant and very public abolitionist orator and journalist posing as a free black citizen in slaveholding America.

On February 1, 2017, President Donald J. Trump made some brief remarks on Black History Month. “Frederick Douglass,” he said, “is an example of somebody who’s done an amazing job, that is being recognized more and more, I notice.” That afternoon in one of the discussion sections of my lecture course at Yale on “The Civil War and Reconstruction Era,” my teaching fellow, Michael Hattem, reports that he read that quotation to the class. Students had just been assigned to read Douglass’s classic first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass. Michael says the class let out an audible collective groan, and one student declared: “My God, he doesn’t know who he was!”

Whatever the current state of President Trump’s historical knowledge, or that of his staff, historians might offer some help for the next time the White House wades into the past for other than nostalgic purposes. Douglass was once called an “illustrious exile” for his triumphant antislavery lecture tours in Ireland, Scotland and England between 1845 and 1847 (while still a fugitive). But even more importantly, he was perhaps America’s most illustrious internal exile. Indeed, until the Civil War all African Americans, slave or free, lived as exiles of a kind in their own land. They were either owned as property, or if free, their civil and political rights were severely restricted.

Until his British friends purchased his freedom from his Maryland owner in 1847, Douglass was for nine years a fugitive slave everywhere he trod. Neither fame nor any security guards protected him from potential recapture and return to slavery. By law he was considered stolen property, a social danger, an alien and illegal black person in white America. Fugitive slaves in the North were viewed by many as a threat to white jobs, a menace to the social and racial order, and a legal challenge to slavery itself. Especially those who could make witness with the compelling oratorical skills of Douglass.

One place to begin to understand our long history with the controversies over immigration is with Douglass. “No man can tell the intense agony,” wrote the memoirist in 1855 while remembering his flight, “which is felt by the slave, when wavering on the point of making his escape. All that he has is at stake; and even that which he has not, is at stake also. The life which he has may be lost, and the liberty which he seeks, may not be gained.”

Throughout modern history, the millions forced to flee as refugees and beg for asylum have felt Douglass’s agony, and thought his thoughts. So many nameless and faceless Syrians or Libyans, Iraqis or Sudanese, Iranians or Serbians have felt the same terrors in deserts, and in the billows of the Mediterranean. And now in airports and immigration offices, on college campuses and in the kitchens of most American restaurants. This is an ancient story; America came to it late, but with historical eyes open this nation knows it well.

B

orn Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, his father likely his owner and his mother, Harriet, likely the owner’s slave, Douglass lived twenty years in bondage on Maryland’s eastern shore and in Baltimore. At age 18 he organized an escape plot with a small “band of brothers” among the slaves on a farm near St. Michaels, Maryland. Foiled and betrayed, he and his comrades were arrested, put in chains and marched several miles to the jail in Easton, the Talbot County seat. As great luck, Douglass’s owner, Thomas Auld, sent his slave back to Baltimore rather than selling him into obscurity in the deep South. Two years later, in a cunning and brave plot hatched with a few friends and with his intrepid fiancée, Anna Murray, Douglass escaped from slavery by train, steamer, and ferryboat to New York City, disguised as a sailor. His story is one of great drama and risk in the face of what he called a sense of “hopelessness” and “loneliness.” But in recollecting these events Douglass left the world an illegal refugee-immigrant’s language of fear and courage. His greatest power always resided in the written and spoken word.

Hope and dread marched on all sides in antebellum America, as they do today in a Jordanian refugee camp, overcrowded boats leaving the Libyan coast, a detention center in Germany, in the border patrol cues at Heathrow Airport, or a customs line at JFK. As his band of potential runaways nervously plotted, “we were confident,” Douglass claimed, “bold and determined at times; and, again, doubting, timid and wavering; whistling like a boy in the graveyard, to keep away the spirits.” Hesitation often became sheer terror of the unknown. As comfortable American citizens with secure passports and the rights of travel contemplate our current crisis over banning people from certain countries, we should listen to Douglass again. “The case … stood thus,” wrote the former slave: “At every gate through which we had to pass we saw a watchman; at every ferry a guard; on every bridge a sentinel; and in every wood, a patrol or slave-hunter. We were hemmed in on every side. The good to be sought, and the evil to be shunned, were flung in the balance.”

Today’s refugees are, of course, seeking new beginnings in wholly new contexts of war, famine, political oppression, and climate crises. But when Douglass had reached safety if not yet legal freedom in New York and New Bedford, Massachusetts, he imagined a universal sensation of what freedom means. He felt “a free state around me, and a free earth under my feet,” wrote Douglass. “What a moment was this for me! A whole year was pressed into a single day. A new world burst upon my agitated vision.” He struggled for appropriate words to capture his feelings. “I felt… as one escaping from a den of hungry lions… Anguish and grief, like darkness and rain, may be described, but joy and gladness, like the rainbow of promise, defy alike the pen and pencil.”

In his greatest speech, on the meaning of the Fourth of July, delivered in 1852, Douglass took aim at what he called the “sacrilegious irony” of American slavery in a republic. Such a brutal contradiction deserved in return his own “scorching irony” and “stern rebuke.” He loved America’s founding ideas so much that he would attack their failure with “fire” and “thunder.”

On the domestic slave trade in people, and especially on the Fugitive Slave Act, which required the return of all runaway slaves by a federal judicial process, Douglass made his auditors see, feel, and even hear the plodding feet of a slave coffle, the “savage yells” of a slave trader, the “shocking gaze” of “slave-buyers” at auctions. Slavery had been “nationalized” by the Fugitive Slave Act, said Douglass. “Your broad republican domain is hunting ground for men.” We are in 2017 and not in 1852, but all is still at stake in how Americans define who and what we are.

Douglass was a magnificent critic of the religious and political hypocrisy at the root of slavery. But no fiercer proponent, no more steadfast lover of America’s founding creeds of natural rights and human equality, spoke to the country in the age of the Civil War. Douglass was a radical, honest patriot. America has always needed its immigrants, external and internal, the legal and the illegal. Is there any voice for the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment right now any more forceful than Khizr Kahn? Was there any greater voice for the meaning of emancipation and the reimagining of the American republic in the 19th century than Douglass? All was and still is at stake.